Computational Design with Myco-Materials

09 Oct 2022

How far can we push a mushroom? Specifically, when we want to use it for fabrication. This might be useful for creating a circular economy, because mushrooms are a type of fungi, and fungi are the planet’s recycling system. In this paper we are sharing what we learned when we used computational methods to grow designs, and this is a high-level overview.

This paper was published at CAADRIA’22Gough, P., Globa, A., & Reinhardt, D. (2022). Computational Design with Myco-Materials. In POST-CARBON, Proceedings of the 27th International Conference of the Association for Computer- Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA) 2022, Volume 2, 649-658. Association for Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia, Hong Kong. https://caadria2022.org/computational_design_with_myco-materials in April 2022, with colleagues at Architecture Design and Planning: Dr Anastasia Globa (who took the photos in the paper) and Associate Professor Dagmar Reinhardt.

Why mushrooms?

Some mushrooms create networks of roots, mycelia, that bind together the substrate that they are breaking down, in nature this might be a tree, or a pile of leaves. This is useful for us, as we can get them to bind together material that is otherwise waste, like sawdust. We can dry this out to make a block of some kind. We wanted to know how detailed we can make this shape. Other studies have shown that there are a range of applications for this kind of myco-material, particularly in architectural settings.

Mushrooms aren’t plants, they’re fungiFungi are a separate kingdom of life to plants and animals. , and the ones we used don’t draw down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. This means that they don’t really increase in volume, like a tree does. The ones we used bind the material together until they are ready to start producing the fruiting body, a mushroom. We don’t allow the mushrooms to grow, because they’ll consume as much of the material as they can. We interrupt this reproductive stage, so that the material can still be utilised. To do this, we want to make the mushroom feel like it’s underground. No fresh air (high carbon dioxide, but still enough oxygen to survive), humid, dark. Then, they will just hang out, grabbing on to more food.

Mycelium growing on acrylic, looking for more food.

The process for us was quite simple:

- Make a mould

- Clean it with disinfectant

- Break up the mushroom material from the grow kit

- Press the mushroom material into the mould

- Allow to grow in dark, warm environment until covered with mycelium

- Remove from mould and leave to grow in the open, so all sides are covered with mycelium

- Dry in very low oven (50 - 80ºC)

The material we used is a Grow-It-Yourself mushroom kitPurchased from Aussie Mushroom Supplies for this project—though, it’s not cheap per cubic cm if you’re making a lot of objects, or a really bulky design. But, for our purposes, it’s reasonable at small scale, and much more reliable than trying to start from sawdust and not grow wild mould in the process. Our research was not about the growing process itself, rather, we wanted to ask what the outcomes are, if we try to make small details from this material.

So we purchased substrate, the mushroom, and also had inclusions, such as used coffee grounds and waste cardboard, which is readily available at our university, and probably most other places of work. Inclusions helped bulk out the material and altered some of its properties.

What can a mushroom do?

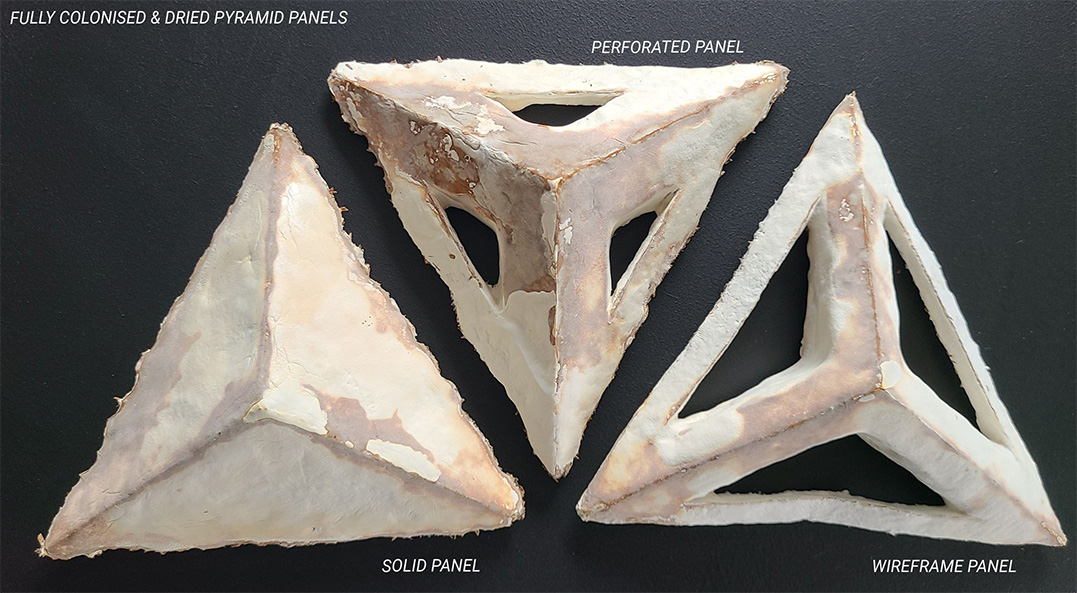

What kind of output do we get, if we make the moulds more and more challenging? To examine this, we did several tests, one of which was the Segment Iterations and another was the Pyramid Panels.

For the segment iterations test, we used computational design tools (grasshopper) to make mouldsCaps made to fit small containers that were 3D printed, with walls of different thicknesses and heights. A major limitation was how to pack the substrate between thin walls at the extreme end. The mycelium will grow between these walls, and may even hold its shape when removed from the mould, but once dried, it’s not very good at holding very thin forms. However, we can have some of these details, as long as the substrate is able to be packed into the void.

3D prints and the grown results.

The pyramid panels also showed that we were able to perforate a structure to reduce the material usage. The triangular edges (see above) are only 150mm, so they’re quite small, but they could be used for repeating panels on a wall, for example.

A Takeaway

These materials are interesting to me as they can be part of a circular economy. They can be aligned with a few principles of the circular economy:

- Keep materials in use for as long as posssible – taking waste (e.g. coffee grounds, waste paper, sawdust) and giving it new value, through these materials

- Technical and natural materials should be able to be separated and returned to their own cycles – that’s what mushrooms have always done, return organic materials to their natural cycles, for reuse! Of course, this should be designed when working with technical features, such as fastening or PCBs etc.

This paper is a demonstration of critical function for myco-materials. There’s still a lot to learn before it gets out of the lab, and I have enjoyed getting to know this material through this process.